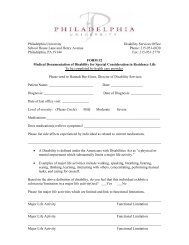

A Chindogu must exist - Philadelphia University

A Chindogu must exist - Philadelphia University

A Chindogu must exist - Philadelphia University

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

A CHINDOGU<br />

MUST EXIST<br />

by Evan Ratliff<br />

photos by Julie Marquart<br />

Don’t Laugh: Those Wacky<br />

Japanese Inventions Are<br />

Making a Comeback.<br />

THUMBZIPPERRING<br />

Designer: Ryan Moore<br />

Problem: Thick digits incapable of<br />

snatching zipper.<br />

Solution: Loop facilitates easy grab.<br />

48

INSTRUCTIONALPLACEMAT<br />

We’d be millionaires. Our idea was bigger than<br />

our Handy-Sun palm-shaped sunscreen applicator<br />

or Jesucles Christian-themed Popsicles. The<br />

device: a thin piece of clear plastic embedded<br />

with what appeared to be broken glass. Stashed<br />

in the trunk of a car, it could be rolled out into a<br />

neighborhood parking space upon departure,<br />

deterring fellow drivers from nabbing coveted<br />

spots. We branded it the Shatter-Park. We<br />

would patent it. Pay dirt would follow.<br />

The Shatter-Park, it turned out, was no idle<br />

barstool concoction. It was a <strong>Chindogu</strong>, in the<br />

same class as breakthroughs like the Hay Fever<br />

Hat (which dispenses toilet paper for nose-blowing),<br />

the Soap Recycler (a vice that mashes leftover<br />

bits together), and the Portable Stoplight (a handheld<br />

traffic signal for pedestrians). These and hundreds<br />

more are the brainchildren of Japan’s Kenji<br />

Kawakami, creator of the decade-old art of “unuseless<br />

invention.” Literally, <strong>Chindogu</strong> means “strange tool” (the<br />

“unuseless” tag refers to objects that, while not exactly<br />

without purpose, barely justify their own <strong>exist</strong>ence). In<br />

short, they are objects whose designs go to extraordinary—and<br />

often ridiculously cumbersome—lengths to<br />

solve everyday problems.<br />

In the early 1990s, Kawakami, now 55, dreamed up all<br />

kinds of unuseless objects while editing a Japanese magazine<br />

that reviewed mail order catalogs. A former<br />

scriptwriter for television and designer of the Japanese<br />

Bicycle Museum, Kawakami published a few of his inventions<br />

and discovered that they were wildly popular<br />

among his readers. Around the same<br />

time, he crossed paths with Dan Papia,<br />

who edited the English-language magazine<br />

Tokyo Journal, and whose claim to<br />

fame was christening the Tokyo Dome<br />

the Big Egg. Papia helped Kawakami<br />

10<br />

of<br />

1ne<br />

2wo<br />

Designer: Emory Krall<br />

Problem: Table setting protocols complex<br />

and difficult to remember.<br />

Solution: Provide detailed template.<br />

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10<br />

TENETS<br />

CHINDOGU<br />

Adapted from Kenji Kawakami’s<br />

101 Unuseless Japanese Inventions:<br />

The Art of <strong>Chindogu</strong><br />

<strong>Chindogu</strong> cannot be for real use.<br />

It is fundamental to the spirit of <strong>Chindogu</strong> that inventions claiming<br />

<strong>Chindogu</strong> status <strong>must</strong> be, from the practical point of view,<br />

(almost) completely useless. If you invent something which turns<br />

out to be so handy that you use it all the time, then you have<br />

failed to make a <strong>Chindogu</strong>. Try the Patent Office.<br />

A <strong>Chindogu</strong> <strong>must</strong> <strong>exist</strong>.<br />

You’re not allowed to use a <strong>Chindogu</strong>, but it <strong>must</strong> be made. You<br />

have to be able to hold it in your hand and think, “I can actually<br />

imagine someone using this. Almost.” In order to be useless, it<br />

<strong>must</strong> first be.<br />

49

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10<br />

TABLETRASHCAN<br />

“CHINDOGU IS THE ANTITHE<br />

PROFESSOR JOSH OWEN.<br />

4our<br />

5ive<br />

Designer: Shaun Smith<br />

Problem: Energy spent transporting<br />

trash from table to receptacle.<br />

Solution: Eliminate distance variable.<br />

Inherent in <strong>Chindogu</strong> is the spirit of anarchy.<br />

3hree <strong>Chindogu</strong> are man-made objects that have broken free from the<br />

chains of usefulness. They represent freedom of thought and<br />

action: the freedom to challenge the suffocating historical dominance<br />

of conservative utility; the freedom to be (almost) useless.<br />

<strong>Chindogu</strong> are tools for everyday life.<br />

<strong>Chindogu</strong> are a form of nonverbal communication understandable<br />

to everyone, everywhere. Specialized or technical inventions,<br />

like a three-handled sprocket loosener for drain pipes centered<br />

between two under-the-sink cabinet doors (the uselessness of<br />

which will only be appreciated by plumbers) do not count.<br />

<strong>Chindogu</strong> are not for sale.<br />

<strong>Chindogu</strong> are not tradable commodities. If you accept money<br />

for one you surrender your purity. They <strong>must</strong> not even be sold<br />

as a joke.<br />

assemble his oddball ideas into a book. Though it was to<br />

be published in English, Papia thought a Japanese name<br />

would give it credibility. “I wanted it to sound like an<br />

ancient art,” he says. The book, 101 Unuseless Japanese<br />

Inventions: The Art of <strong>Chindogu</strong>, appeared in 1993. Spurred<br />

by healthy sales, Papia and Kawakami issued 99<br />

More Unuseless Japanese Inventions two years<br />

later. The books spawned the formation of<br />

<strong>Chindogu</strong> clubs around the world and led to the<br />

founding of the International <strong>Chindogu</strong><br />

Society—the paperback of the first edition<br />

claims the organization “10,000 strong”—<br />

and turned Kawakami into a minor celebrity<br />

in Japan.<br />

After the second book’s publication, though,<br />

Papia and Kawakami were split over the movement’s<br />

philosophical direction. In the U.S., talks with David<br />

Letterman’s Late Show fell through, and plans for 101<br />

Unuseless American Inventions, never got off the ground.<br />

Though Papia had already begun moving on to other<br />

things, he was chagrined by the winnowing of interest. He<br />

had big plans for <strong>Chindogu</strong>, envisioning it as a participatory<br />

design revolution for the masses. “My goal was to get<br />

the word into the dictionary, like karate and karaoke and<br />

other Japanese words,” he says. “I wanted to see it catch<br />

on as an art form,” whereas Kawakami, Papia complains,<br />

“wanted it to just sort of be his.” Not long after the second<br />

book came out, Papia returned to the States, where he<br />

enrolled in film school and started a new life as a screenwriter.<br />

Meanwhile, Kawakami rode out his notoriety in<br />

Japan. <strong>Chindogu</strong> seemed confined to the Table<br />

Trash Can of history.<br />

Not entirely. In the classrooms of American<br />

design schools, the art of unuseless design is<br />

enjoying an unexpected revival. Josh Owen, a<br />

professor of industrial design at the <strong>University</strong> of<br />

<strong>Philadelphia</strong>, employs <strong>Chindogu</strong> as a teaching tool to force<br />

students to solve everyday problems with everyday materials.<br />

<strong>Chindogu</strong>, he says, “is the antithesis of the styledriven<br />

approach. Students are freed from market research,<br />

from ‘taste-based user scenarios.’”<br />

In their projects, Owen and his students adhere strictly<br />

to the 10 Tenets of <strong>Chindogu</strong>, laid out by Kawakami in his<br />

first book (see sidebar, page 49). Among these: “<strong>Chindogu</strong><br />

cannot be patented or sold,” “<strong>Chindogu</strong> <strong>must</strong> <strong>exist</strong>,”<br />

and “<strong>Chindogu</strong> are never taboo.” Most important,<br />

they <strong>must</strong> be “tools for everyday life” that embody a<br />

“spirit of anarchy—the freedom to be almost useless.” In<br />

Owen’s thinking, a <strong>Chindogu</strong> is “that long-winded ‘better<br />

mousetrap’ that takes too many steps to produce an<br />

effect.” Indeed, Owen and his students carefully vet each<br />

50

SIS OF STYLE,” SAYS DESIGN 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10<br />

6ix<br />

Humor <strong>must</strong> not be the sole reason for<br />

creating <strong>Chindogu</strong>.<br />

WATCHVIEWJACKET<br />

The creation of <strong>Chindogu</strong> is fundamentally a problem-solving<br />

activity. Humor is simply the byproduct of finding an elaborate<br />

or unconventional solution to a problem that may not<br />

have been pressing to begin with.<br />

7even<br />

<strong>Chindogu</strong> are not propaganda.<br />

<strong>Chindogu</strong> are innocent. They are made to be used, even though<br />

they cannot be used. They should not be created as a perverse or<br />

ironic comment on the sorry state of mankind.<br />

8ight<br />

<strong>Chindogu</strong> are never taboo<br />

The International <strong>Chindogu</strong> Society has established certain standards<br />

of social decency. Cheap sexual innuendo, humor of a<br />

vulgar nature, and sick or cruel jokes that debase the sanctity<br />

of living things are not allowed.<br />

Designer: Trina Lefevre<br />

Problem: Sleeve blocks view of watch.<br />

Solution: Permanent window allows<br />

unimpeded access.<br />

TIEBIB<br />

Designer: Jarrett Seng<br />

Problem: Saucy foods splatter<br />

fancy work clothes.<br />

Solution: Stealthy bib folds<br />

out of unassuming tie.<br />

More<br />

<strong>Chindogu</strong>,<br />

please.<br />

51

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10<br />

Designer: Marc Caccavo<br />

Problem: Risk of splashes during<br />

plunging action.<br />

Solution: Allows for plunging while<br />

toilet lid is down.<br />

9ine<br />

10en<br />

<strong>Chindogu</strong> can never be patented.<br />

<strong>Chindogu</strong> are offerings to the rest of the world—they are not<br />

therefore ideas to be copyrighted, patented, collected, and<br />

owned. As they say in Spain, Mi <strong>Chindogu</strong> Es Tu <strong>Chindogu</strong>.<br />

<strong>Chindogu</strong> are without prejudice.<br />

CHINDOGU<br />

STAYDRYPLUNGER<br />

<strong>Chindogu</strong> <strong>must</strong> never favor one race or religion over another.<br />

Young and old, male and female, rich and poor—all should have<br />

a free and equal chance to enjoy each and every <strong>Chindogu</strong>.<br />

proposed <strong>Chindogu</strong> to make sure it’s<br />

not too useful. Some of the projects<br />

that made the cut include the Watch<br />

Window Jacket (with a section cut from the<br />

sleeve for reading your watch), the Table<br />

Trash Can (with a hole at the center for waste disposal),<br />

and the Carpet Remnant Carpet (created by fastening<br />

together scraps and samples). “The tenets,” Owen<br />

says, “are extremely effective in dictating a procedure for<br />

making an object that is really devoid of any sort of superficial<br />

style.”<br />

Owen incorporates the spirit of unuselessness into his<br />

own work, which often features renewed takes on common<br />

objects. His latest creation, the Knock-Off Lamp, sold by<br />

Bozart, is a bowling pin light that turns off when tipped<br />

over. “That’s where product design gets fun,” he<br />

says, “when it causes you to rethink the ordinary.”<br />

Don Norman, a professor of computer<br />

science at Northwestern <strong>University</strong> and the<br />

author of Design of Everyday Things, recommends<br />

Kawakami’s books to his students.<br />

“It appeals to my bizarre sense of<br />

humor,” Norman says. While <strong>Chindogu</strong><br />

are useless, or nearly so, they hit a<br />

Seinfeld-esque, design-about-nothing<br />

nerve—think Kramer’s coffee table book as coffee table—<br />

highlighting the absurdity of daily life. “You can’t come up<br />

with these things without actually having thought about<br />

what people do throughout the day,” Norman says. “It<br />

exposes real problems, often through silly solutions.”<br />

A decade after the first <strong>Chindogu</strong> book appeared, it has<br />

become required reading among industrial designers.<br />

“The wonderful thing about <strong>Chindogu</strong> is you think to yourself,<br />

‘Well, that could work,’” Owen says. Kawakami,<br />

meanwhile, has produced several Japanese-language follow-ups<br />

to his first edition, and of late has been working<br />

with Hollywood producers on a live television show à la<br />

Iron Chef. Papia, for his part, now presides as president of<br />

the International <strong>Chindogu</strong> Society. He still receives submissions<br />

and has been collecting them for another book.<br />

Greatest hits thus far include Exercise Chopsticks for<br />

strengthening fingers and Pitstopper sponges that keep<br />

your armpits dry.<br />

The art of <strong>Chindogu</strong> perseveres, but so far the fortunes<br />

from our Shatter-Park have yet to materialize. The truth is<br />

we never got around to making it. But in a remarkable<br />

example of spontaneous generation, one of Owen’s students<br />

did. He created a broken glass-like rollout called<br />

the Space Saver made from a special rubber developed<br />

by a Hollywood props company. Faithful to<br />

the spirit of <strong>Chindogu</strong>, he never marketed it.<br />

52

shirts available at www.readymademag.com